Greater Roadrunner

About

Darting through the thornscrub from the Mississippi river to the Pacific Ocean is a charming bird known as the greater roadrunner. The inspiration for cartoons and mascots the world over, this two-foot-long bird is as famous as it is misunderstood. It’s not purple, though its iridescent feathers do look like rainbows in the light, and their soft coos and beak clatters don’t sound at all like a “meep meep” — so let’s dive in here to learn about real-life roadrunners!

Adaptations

Even though roadrunners can fly, they don’t do it often, not even to migrate. This means they need to be prepared to survive within the Sonoran Desert — through the extreme heat of summer, the freezing cold of winter, and all the dry times in between. On cold winter nights they go into torpor — a state where their body slows down and drops a couple of degrees, and their need for food is reduced. Think of this as an energy-saving mode for freezing nights; then when the sun rises, they spread their feathers and catch some rays to warm back up. In the summer, they avoid the hottest part of the day altogether and become crepuscular instead of diurnal, meaning they’re active around dawn and dusk when the temperatures are more manageable.

Roadrunners also have a special gland that helps them excrete salt. Many seabirds have a similar gland, but in the case of the roadrunner, it helps them save water! By filtering excess salt out of the blood, this gland helps the bird’s kidneys not need to pee as much.

Food Web

Greater roadrunners will eat almost anything they can catch, which is a long list! Their prey includes insects, scorpions, spiders, tarantulas, and even small vertebrates like rodents, lizards, and snakes! They slam their prey on the ground to make sure it’s safe to eat and not still alive. Even though they hunt about 90% of their food, roadrunners are opportunistic enough to eat plant materials like seeds and berries, making them omnivores.

While these birds are incredible predators, they are nowhere near the top of the food chain! Large apex predators like hawks, bobcats, and coyotes have been known to prey upon adult roadrunners. Other species like raccoons are known to eat their eggs. Additionally, humans have brought domestic cats into the desert, and roadrunners are increasingly being killed by these critters like so many other native birds.

Habitat and Range

Greater Roadrunners are best adapted to dry and open ecosystems, but they are adaptable animals that can live in many different habitats. They can be found everywhere from the pine forests of northern California to the swamps of the gulf coast, but they prefer scrubland, grassland, and desert environments.

If you really want to see a greater roadrunner in the wild, your best chances will be in the Sonoran Desert, where they can best make use of their water-saving adaptations and speed.

Family Life

Baby roadrunners hatch in a clutch of 2-5 eggs in a small nest just a few feet off the ground. They’re fed by their parents for about 3 weeks. After that, they’re old enough to tag along with their parents and learn how to hunt and forage.

When greater roadrunners are 3 years old, they’re ready to start their own families. Males will present lizards to females, and if they accept, the two will spend the rest of their lives together. They’ll work together to build the nest, catch the food, and teach their hatchlings to survive in the wild.

Glossary

- Torpor:

- An “energy-saving” mode for animals brought on by low temperatures or lack of food. They use less energy because their body temperature is lowered, and they do not process food as quickly.

- Crepuscular:

- Being most active in the mornings and evenings.

- Diurnal:

- Active during the day and asleep at night.

- Omnivore:

- An organism that eats both plant and animal material.

- Brood Parasitism:

- A bird lays their eggs in a different bird’s nest and allows that bird to incubate and raise their hatchlings.

Fun Facts

- Roadrunners have small wings, so they can’t fly very well. They prefer to run and glide.

- Roadrunners leave X-shaped tracks, making it difficult to tell which direction they were heading!

- If a snake caught by a roadrunner is too long to eat all at once, they will let it hang from their mouth, slowly slurping it up as they digest until it’s gone — kind of like slow-motion spaghetti!

- Greater roadrunners are also known as California ground cuckoo and chaparral bird.

- Roadrunner eggs have been reported in the nests of other birds, suggesting occasional brood parasitism like other birds in the Cuckoo group!

Conservation

- IUCN Conservation Status: Least Concern

- As the west continues to grow more arid, the roadrunner’s range is gradually extending north, only to be reduced annually by cold winters.

Conservation Index

At The Museum

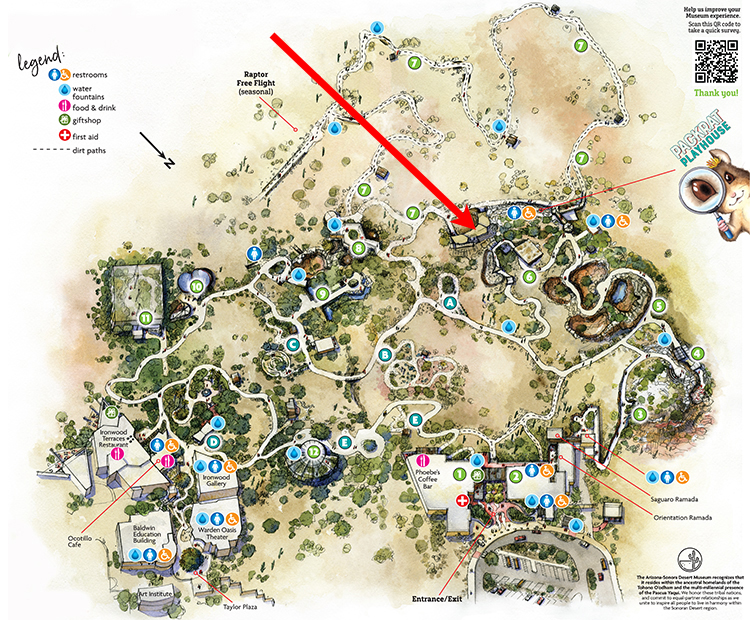

View on Map

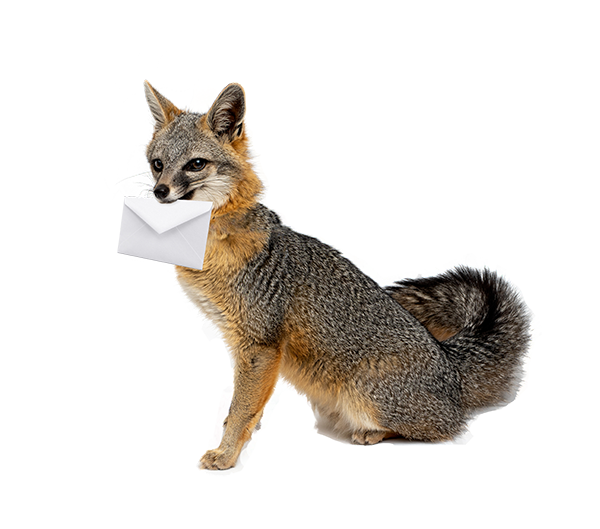

Churro (male) is currently in Life on the Rocks, sharing an enclosure with his jackrabbit friend, Cantaloupe, accessible along paved paths year-round.

Like many animals at the Desert Museum, Churro is unable to live in the wild. In his case it’s because he’s blind in one eye.