Definition of a Succulent

Mark Dimmitt, Director of Natural History

Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

Classifying plants as succulent or nonsucculent is problematic. Regional floras

and popular books on succulents are all vague at defining what makes a plant

a succulent. For example, Rowley (1978) concluded only that many plants are difficult

to categorize as to succulence. Popular publications on succulents often ignore

clearly succulent plants such as many orchids and bromeliads simply because most

succulent collectors don't grow them (e.g., Eggli 2001). Plant physiologists

and systematists tend to be similarly noncommittal. Some authors use the term

semisucculent for those plants with less obvious succulent characteristics, but

this still leaves the separation between semisucculent and nonsucculent undefined.

Von Willert et al. (1992) represents the only source we know of that attempts

a concise description. They define a succulent as any plant that possesses a

succulent tissue, and further specified a succulent tissue as "... a living tissue

that... serves and guarantees a ...temporary storage of utilizable water, which

makes the plant... temporarily independent from external water supply...". The

authors recognized a subcategory of xerophytic succulents, which excludes halophytic

succulents (salt-tolerant plants that often grow in saline wetlands) and most

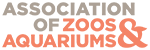

geophytes (plants with their perennating organs below ground, e.g., potato, Jatropha

macrorhiza, and most plants that are colloquially called "bulbs" in

horticulture).

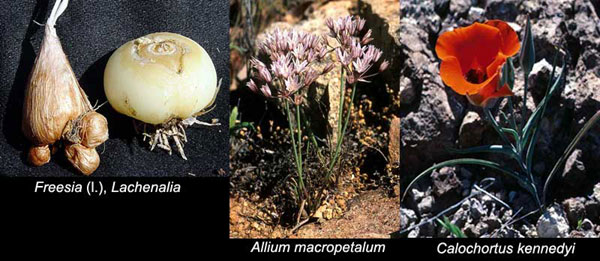

Examples of bulbous geophytes.

(The Freesia is technically a corm; the others are true bulbs.) The fleshy parts of most "bulbs"

serve more for food storage than water storage; they produce above-ground

growth only after the soil is moistened. However, some bulbous geophytes

sprout before the beginning of the rainy season or maintain green foliage

well into the dry season; we would classify these as succulents. The

succulent tissues of halophytes and of most geophytes serve functions

other than to support growth when soil moisture is unavailable. This

definition of the term xerophytic succulent still leaves the status

of a number of plants in question.

Some questionably succulent species

(click on images for additional information and more photos)

|

matacandelilla, giant

cane milkweed

Asclepias albicans |

tescalama, rock fig

Ficus palmeri |

|

torote prieto

Bursera hindsiana

|

ocotillo macho

Fouquieria macdougalii |

|

calabacilla, coyote

gourds

Cucurbita spp.

|

matacora

Jatropha cuneata

|

|

liga

Euphorbia xantii

|

mistletoe

Psittacanthus sonorae |

We classify all of the above except Psittacanthus as succulents;

this parasite is rather fleshy, but it has a dependable supply of water as long

as its host is alive.

Calabacilla and many other cucurbits have large tuberous roots that have

considerable moisture as well as copious starch reserves. A sample of

Cucurbita foetidissima root was 81% water. They produce leafy shoots,

flowers, and fruits well in advance of seasonal rains. This trait is itself

insufficient to separate calabacilla from clearly nonsucculent plants

such as manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.), which sprout from woody

crowns immediately after dry-season fires. Metabolizing stored starch

in manzanita crowns and roots generates enough water to support growth

in the fall before the winter rains begin. Though tuberous-rooted cucurbits

may also produce some of their water from starch breakdown, the high free

water content along with their ability to produce growth even after a

year without rain leads us to classify them as xerophytic root succulents.

|

|

| Cucurbita foetidissima root

with section cut out to show succulent tissue |

Manzanita (Arctostaphylos sp.)

sprouting from the root crown 2 months after a fire |

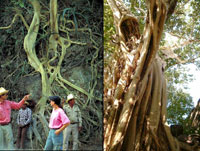

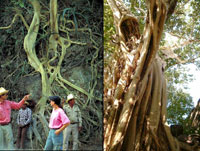

The growthform of tescalama (desert rock fig, Ficus petiolaris palmeri) is intermediate

between a woody tree and a stem succulent. The fact that seedlings can

establish on exposed rock faces (saxicole) in the desert indicates that

this species has adaptations that typical woody trees lack. The caudex

of a young tescalama contained 68% water, somewhat more than stems of nonsucculent

trees such as foothill palo verde (Parkinsonia microphylla, 53%

water). Tescalama does not appear to have CAM. We tentatively classify

it as a succulent based on its marginally elevated water content and

lifestyle. (A closely related species, F. petiolaris petiolaris, occurs

in tropical deciduous forest, a community comprised of so many similarly

semisucculent trees of numerous species that the forest cannot support

a fire.)

|

|

|

| Ficus palmeri (rock fig), in cultivation |

Parkinsonia microphylla (foothill palo

verde) |

Ficus petiolaris (rock fig) |

Most species of Fouquieria exhibit a woody

shrub growthform, albeit a strange one. But they have a clearly succulent lifestyle: very

shallow roots and the capacity to produce functioning leaves within

2 days after a light rainfall (ca. 7 mm). The thin subcutaneous layer

of moist tissue in these plants is succulent in nature (Henrickson,

1969a and b, 1972). The rapid leaf production indicates the presence

of an undescribed non-CAM idling metabolism (Dimmitt

2000).

|

|

|

Fouquieria on a sand dune with shallow roots exposed by

wind erosion |

Fouquieria leaves, 2 days after a rain |

The broken spine reveals a subcutaneous layer of moist

tissue |

REFERENCES

Dimmitt, Mark A. 2000. Flowering plants of the Sonoran Desert. In: Phillips,

Steven J. & Patricia W. Comus (eds.). A Natural History

of the Sonoran Desert.

University of California Press.

Eggli, U. (ed.) 2001. Illustrated Handbook of Succulent Plants: Monocotyledons.

Springer.

Henrickson, J. 1969a. An introduction to the Fouquieriaceae. Cactus and Succulent

Journal (U.S.) 41:97-106.

Henrickson, J. 1969b. The succulent Fouquierias. Cactus and Succulent Journal

(U.S.) 41:178-184.

Henrickson, J. 1972. A taxonomic revision of the Fouquieriaceae. Aliso 7:439-537.

Rowley, G. 1978. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Succulents. Leisure Books (publ.

by Salamander Books Ltd.).

Von Willert, D. J., B. M. Eller, M. J. A. Werger, E. Brinckmann, and H.-D. Ihlenfeldt.

1992. Life Strategies of Succulents in Deserts with Special Reference to the

Namib Desert. Cambridge University Press, London.

|