from sonorensis, Volume 16, Number 2 (Fall 1996)

David A. Kring

David A. KringSenior Research Associate

Lunar and Planetary

University of Arizona

Anna M. Domitrovic

Mineralogist

Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

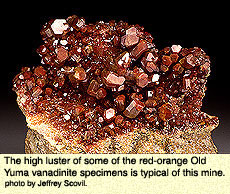

While today the Tucson Mountains are largely protected within the confines of the Saguaro National Park and the Tucson Mountain Park, they once were mined extensively for copper, gold, silver, lead and other metallic elements. Scattered through the mountains are remnants of over 120 mines, prospects and quarries, many of them hidden beneath the tangled roots and branches of palo verde trees (so do not wander off marked trails!). These mining activities, plus the work of academic geologists and private mineral collectors, have produced a dizzying array of over 80 minerals, including some of the world's most spectacular fiery-red vanadinite specimens.

Most of the ores and minerals in the Tucson Mountains, like those in many mountain ranges within the Sonoran Desert, were produced when hot magmatic fluids concentrated metals and precipitated metalliferous sulfides, some of which were then altered by additional fluids to produce an even wider variety of exotic mineral specimens. Metal-rich magmatic fluids are the by-products of volcanism. In the Tucson Mountains there have been three episodes of volcanism, the oldest remnant of which is a 160 million-year-old mid-Jurassic igneous rock called the Museum Porphyry, because it sits near the ASDM on Brown Mountain. Most of the mineralization, however, appears to be related to the second episode of volcanism which swept through the region 70 million years ago near the end of the Cretaceous Period.

At that time, southern Arizona was saturated with a belt of towering volcanic peaks and a sea of volcanic vents. In the Tucson Mountains, a huge 20 x 25 kilometer volcanic caldera (crater) was created when a 4- to 5-kilometer thick sequence of hot volcanic ash poured out onto the surface of the surrounding terrain. Toward the end of this caldera-forming series of eruptions, several plumes of subsurface magma rose and began to penetrate the overlying sequence of rocks. These magmas carried the copper-, gold- and silver-bearing siliceous fluids that eventually deposited ore-bearing minerals.

At that time, southern Arizona was saturated with a belt of towering volcanic peaks and a sea of volcanic vents. In the Tucson Mountains, a huge 20 x 25 kilometer volcanic caldera (crater) was created when a 4- to 5-kilometer thick sequence of hot volcanic ash poured out onto the surface of the surrounding terrain. Toward the end of this caldera-forming series of eruptions, several plumes of subsurface magma rose and began to penetrate the overlying sequence of rocks. These magmas carried the copper-, gold- and silver-bearing siliceous fluids that eventually deposited ore-bearing minerals.

The largest resurgent magma plume crystallized into the Amole granite and granodiorite which occupies a large area of the Saguaro National Park. Before this magma body cooled, it thermally metamorphosed and chemically altered the surrounding rocks. Some of the most dramatic changes occurred where the magma and magmatic fluids encountered limestone. In these areas one can find abundant evidence of mineralization, including thumb-sized garnet nodules. In the early 1900s, the Gould Camp, fully equipped with a mess hall and blacksmith shop, was built near King Canyon in one of these contact metamorphosed zones. Copper sulfide minerals with traces of silver were successfully recovered from the mine, which had a main shaft more than 300 feet deep, a 60-foot tunnel, a 70-foot tunnel and several other smaller shafts.

Additional mines were built near similar, but smaller, magmatic intrusions in the Sedimentary Hills along Kinney Road and Saginaw Hill along Valencia Road where prospectors found the sulfide minerals chalcopyrite, galena, pyrite, pyrrhotite and sphalerite. At Saginaw, the primary sulfide minerals were often altered to a series of copper oxides, carbonates and phosphates. This oxidized zone is one of the few localities in the world where peacock-blue cornetite is found, along with other copper-rich minerals.

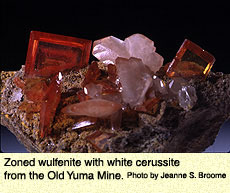

Magmatic fluids associated with the Amole pluton (and perhaps other hydrothermal fluids) also penetrated and altered a thick sequence of lava flows and sedimentary rocks that had formed ponds in the north end of the collapsed caldera. Mineralization was extensive here as fluids concentrated and deposited lead-rich ores and eventually vanadium-rich mineral specimens in a network of veins. The most famous mine in this area is the Old Yuma Mine, which originally opened in 1885. Along with galena, the dominant ore-bearing lead mineral, caches of beautiful vanadinite and wulfenite crystals were found in pockets carved by earlier corrosive fluids. The colors of vanadinite are striking, ranging from fiery red to brick red or yellow. Wulfenite crystals are usually bright yellow to orange to red in color, but rare black crystals also were found with several other exotic minerals.

Magmatic fluids associated with the Amole pluton (and perhaps other hydrothermal fluids) also penetrated and altered a thick sequence of lava flows and sedimentary rocks that had formed ponds in the north end of the collapsed caldera. Mineralization was extensive here as fluids concentrated and deposited lead-rich ores and eventually vanadium-rich mineral specimens in a network of veins. The most famous mine in this area is the Old Yuma Mine, which originally opened in 1885. Along with galena, the dominant ore-bearing lead mineral, caches of beautiful vanadinite and wulfenite crystals were found in pockets carved by earlier corrosive fluids. The colors of vanadinite are striking, ranging from fiery red to brick red or yellow. Wulfenite crystals are usually bright yellow to orange to red in color, but rare black crystals also were found with several other exotic minerals.

At about the same time the ores of the Old Yuma Mine were being deposited, a swarm of magmatic intrusions, called the Silver Lily Dikes, were injected through the floor of the caldera and the overlying sequence of volcanic ashes and breccias. These intrusions were only a few meters wide, but cut across the Tucson Mountains for distances up to 6 kilometers. A series of mines were sunk along the contacts between the dikes and adjacent sedimentary rocks, including at least one mine that used Spanish silver mining techniques that had been developed in arid portions of Mexico. By 1893 (and perhaps earlier), a small cluster of buildings called the Amole Camp had been established to support the mines.

While the Gould, Saginaw, and Amole camps have long since been abandoned, and the mines in the mountains have long since been deserted, they produced some brilliant mineral specimens. These specimens provide us with a unique glimpse of the natural history of the Tucson Mountains and, at the same time, are a legacy of an interesting period in human history.